A Brief Architectural History of The Roman Pantheon

Photograph of the coffered dome and oculus in the Pantheon. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

I can recall the unusual feeling I had when looking up at the oculus in the Pantheon. The day that I visited Rome, it was overcast with a light drizzle. Inside the space, the light was low, and the details of the coffers and columns were difficult to make out. The age of the structure emanated a feeling that felt very different from any other church, basilica, or temple I had visited. As I walked towards the center of the space, a perfectly formed cylindrical column of rain entered through the oculus. It was an experience that I will never forget.

As a young architecture student in university, we studied the Pantheon through drawings and photographs. However, it is impossible to understand the grandeur and scale until you visit the building. As I walked through the building, I immediately understood why this structure holds such high esteem in the history of architecture. After visiting the Pantheon, I needed to learn more about this iconic structure.

HISTORY OF THE PANTHEON

The original temple was commissioned by the son-in-law of Ceasar Agustus, Marcus Agrippa. After several fires, the temple was almost fully reconstructed during the reign of Emperor Hadrian between 118 and 125 A.D. Hadrian had an affinity for traveling and sought to visit beautiful architecture from many parts of the world. The original purpose of the Pantheon was to be a temple dedicated to all the Roman gods in ancient times. He would combine elements from both Greece and Etruscan styles in the Pantheon many of which were observed on his travels. The Pantheon remains one of the best-preserved ancient monuments from the Roman Empire.

At the time the Pantheon was constructed, it was unique because of the size and the span of the dome. Vaulting a space the size of the Pantheon would have been an unprecedented achievement.

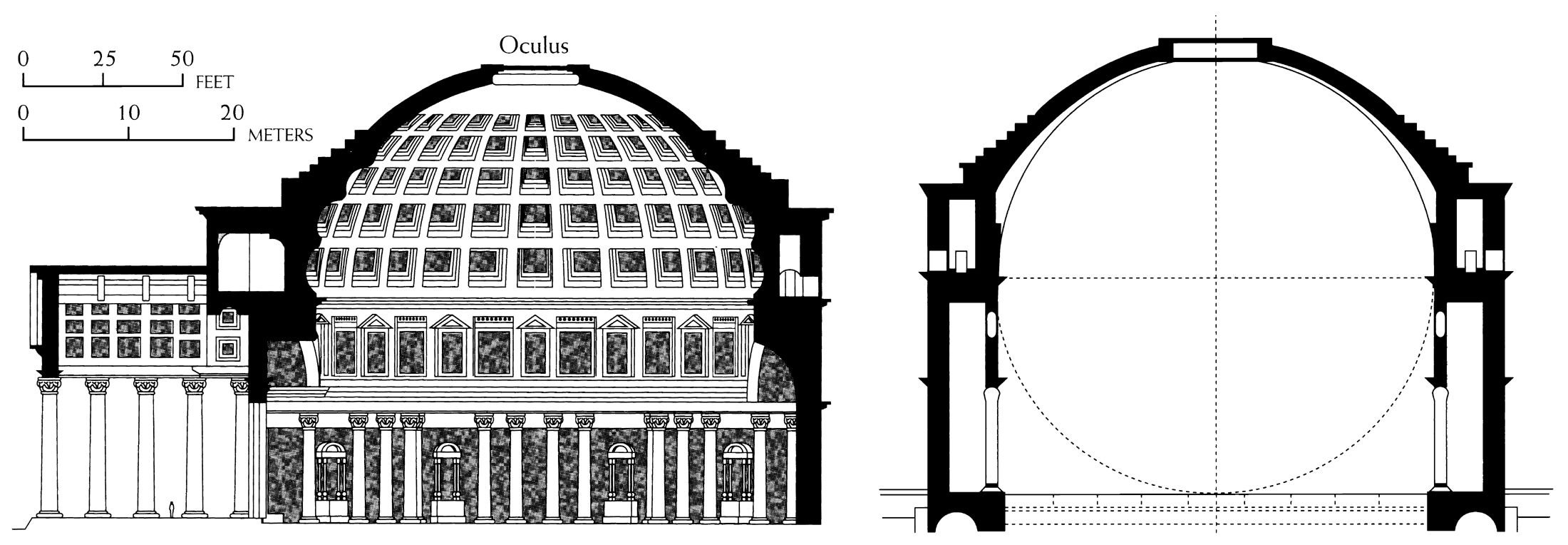

There are four main components of the Pantheon. They are the portico, transitional block, drum, and dome. These elements can be found in other Roman buildings such as baths, tombs, and basilicas, however, there was not a building that incorporated all four elements on such a grand scale.

THE PORTICO

The Portico is the entry “porch” where you enter the Pantheon. The Portico faces the Piazza della Rotonda and is comprised of 16 granite columns, each measuring roughly 40 ft tall and 15 ft in circumference. The columns support a massive pediment with text that can be translated to "Marcus Agrippa, the son of Lucius, three times consul, built this." The Portico is an apparent reference to Greek Architecture. Studies suggest that the columns in the portico were quarried in Egypt as single pieces of stone and transported across the Mediterranean sea to Rome. Many eyebrows have been raised regarding this feat.

Over centuries of construction, demolition, wars, and daily life, layers of ruble were built up and the elevation of the Piazza and surrounding streets were raised. Today, you can experience this phenomenon as you step down from the Piazza into the portico of the Pantheon.

Photograph of the portico of the Pantheon. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE DRUM

The Drum of the Pantheon is the vertical cylinder that creates the base on which the dome sits. The Drum of the Pantheon measures approximately 108 feet tall and 21 feet thick at the base. The Romans understood that this thickness was required to resist the horizontal thrusting forces of the dome above. With a hemispherical dome, the horizontal thrusting forces can easily push the drum wall outwards, forcing the dome to collapse.

There is a series of circular "cells" cut out from the thickness of the drum wall. By removing large masses of the Drum, the Romans were able to conserve material resources while still maintaining the structural integrity of the drum to support the dome.

Photograph of the entry door to the Pantheon. Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

The drum is constructed out of concrete formed within a brick shell. The Romans laid brick as formwork then poured the thick wall of within the shell. The brick remained as a finish material in several areas, however, most of it would have been cladded in marble. The concrete used in the Pantheon is a mixture of lime and pozzolana. Pozzolana is a volcanic powder that has many advantageous qualities. One of the main benefits is the material's ability to cure in the absence of air and even underwater. In the case of the Pantheon, the concrete inside of the 21-foot thick walls at the base of the drum would still be able to cure with minimal to no exposure to air. Layers of large aggregate were laid in the concrete pours, with some aggregate pieces being the size of a softball.

At the base of the drum, the concrete is filled with heavier brick aggregate and tufa to help resist the gravity loads of the structure it supports. Moving up in the structure, the concrete mixture would include materials such as pumice and volcanic slag. Volcanic slag is a highly porous material filled with air pockets making it incredibly light while still maintaining its structural integrity. When placed in water, the material floats.

Photograph of the interior drum and coffered dome in the Pantheon. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE DOME

Many buildings in Rome used the concept of a hemisphere sitting on top of the drum. However, none had achieved the massive scale until the Pantheon. The dome of the Pantheon spans an impressive 142 feet. The dome's radius is equal to the drum's vertical height and horizontal width. The mathematical precision of this is remarkable in the actual structure.

The dome was constructed out of light volcanic material to reduce the structure's weight. There were three main advantages of adding pumice and volcanic slag to the concrete mixture. The lightness of the structure, the reduced outward thrust, and reduces the compression forces on the layers below. During construction, the dome was constructed with wooden scaffolding. The scaffolding supported wooden molds that held the concrete. When the concrete was cured, the scaffolding and wood forms were removed, leaving the dome suspended across the drum.

As the dome rises in height, the dome shell's thickness decreases, again to reduce weight. Coffers were used on the interior of the dome shell, which channels the forces through ribs, again reducing overall weight. A nine-meter diameter oculus sits at the top of the dome, completely open to the sky above.

A layer of plaster finishes the inside of the dome and coffers. There was originally a layer of bronze tiles on the dome's exterior. A layer of lead replaced it. Because the structural composition of the dome remains intact, there is limited access to see the internal makeup and layering inside.

Photograph of the interior drum and coffered dome in the Pantheon. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE INFLUENCE OF THE PANTHEON

Nearly a millennium later, Brunelleschi would successfully construct a dome larger than the Pantheon in the 15th century. Prior to designing the dome in Florence, it is documented that Brunelleschi spent a large amount of time in Rome studying ancient ruins and most certainly visited the Pantheon. Although Brunelleschi’s dome would be built from brick rather than cast in concrete, he would extract many principles from the Pantheon dome to use in his structure.

Frank Lloyd Wright had a general interest in classical architecture. His Unity Temple in Oak Park reflects many of the same principles as the Pantheon. At the end of his career, he was quoted as stating that the Guggenheim Museum he designed in New York was "my Pantheon." The nod to the Pantheon in his work and references clearly suggest his admiration for the structure.

Louis Kahn also embodied many principles from the Pantheon in his architectural philosophies and projects. Similar to Brunelleschi, Kahn would travel to Rome to study the local architecture during the middle of his career. Many have said that this experience changed the trajectory of his career and was instrumental in producing such successful buildings after the experience. His buildings, such as the Yale Center for British Arts, the National Assembly of Bangladesh, and the Exeter Library, show clear references to the principles of the Pantheon.

Photograph of the entry door to the Pantheon. Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Why is the Pantheon Important?

No other building has been referred to or echoed in architecture more than the Pantheon. Architects worldwide have extracted principles from this building throughout the course of history. It is one of the most used precedents in architecture. This alone makes the building worthy of acknowledgment and study, however, for me, this is not what makes this building special.

The atmosphere, quality of light, and scale are what left a lasting impact on me. I was stunned at the unique atmosphere within the building. It is a “must-see” site if you travel to Rome. Access to the Pantheon is free with booking required on weekends and holidays.

We hope you enjoyed reading the article. Please notify us if you see any errors or inconsistencies. Our goal is to provide the most informative and accurate material possible.

Photograph of the portico and drum of the Pantheon. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

References:

Marder, Tod A., and Wilson Mark Jones. The Pantheon: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

King, Ross. Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Photograph of the portico of the Pantheon. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Notre Dame Cathedral had the power to embed itself into more than just the cityscape. It made its way into the hearts of the people of Paris. When the Cathedral was engulfed in flames on April 15th, 2019, we were reminded that the architecture around us impacts our lives beyond functionality. Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses the history, architecture, and the architectural power of Notre Dame Cathedral.